5 Site Structure

Semantic Content Markup

Proper use of html is the key to getting maximum flexibility and return on your investment in web content. From its earliest origins, html was designed to distinguish clearly between a document’s hierarchical outline structure (Headline 1, Headline 2, paragraph, list, and so on) and the visual presentation of the document (boldface, italics, font, type size, color, and so on). html markup is considered semantic when standard html tags are used to convey meaning and content structure, not simply to make text look a certain way in a browser.

This semantic approach to web markup is a central concept underlying efficient web coding, information architecture, universal usability, search engine visibility, and maximum display flexibility. Web content is accessed using web browsers, mobile computing devices of all kinds, and screen readers. Web content is also read by search engines and other computing systems that extract meaning and context from how the content is marked up in html.

<h1>This is the most important headline</h1>

<p>This is ordinary paragraph text within the body of the document, where certain

words and phrases may be <em>emphasized</em> to mark them as

<strong>particularly important</strong>.</p>

<h2>This is a headline of secondary importance to the headline above</h2>

<p>Any time you list related things, the items should be marked up in the form of a list:</p>

<ul>

<li>A list signals that a group of items are conceptually related to each other</li>

<li>Lists may be ordered (numbered or alphabetic) or unordered (bulleted items)</li>

<li>Lists may also be menus or lists of links for navigation </li>

<li>Cascading Style Sheets can make lists look many different ways</li>

</ul>

Even in the simple example above, a search engine would be able to distinguish the importance and priority of the headlines, discover which keywords were important, and identify conceptually related items in list form. A Cascading Style Sheet designed particularly for mobile phones could display the headlines and text in fonts appropriate for small screens, and a screen reader would know where and how to pause or change voice tone to convey the content structure to a blind reader.

HTML document structure

Properly structured html (or xhtml) documents may contain the following elements:

- html document structure (

<head>,<body>,<div>,<span>) - Text content

- Semantic markup to convey meaning and content structure (headlines, paragraph text, lists, quotations)

- Visual presentation (css) to make content look a certain way

- Links to audiovisual content (gif, jpeg, or png graphics, QuickTime or other media files)

- Interactive behavior (JavaScript, Ajax elements, or other programming techniques)

Document structure

In properly formed html, all web page code is contained within two basic elements:

- Head (

<head>…</head>) - Body (

<body>…</body>)

In the past these basic divisions in the structure of page code were there primarily for good form: strictly correct but functionally optional and invisible to the user. In today’s much more complex and ambitious World Wide Web, in which intricate page code, many different display possibilities, elaborate style sheets, and interactive scripting are now the norm, it is crucial to structure the divisional elements properly.

The <head> area is where your web page declares its code standards and document type to the display device (web browser, mobile phone, iPod Touch) and where the all-important page title resides. The page head area also can contain links to external style sheets and JavaScript code that may be shared by many pages in your site.

The <body> area encompasses all page content and is important for css control of visual styles, programming, and semantic content markup. Areas within the body of the page are usually functionally divided with division (<div>) or span (<span>) tags. For example, most web pages have header, footer, content, and navigation areas, all designated with named <div> tags that can be addressed and visually styled with css.

The html document type declares which version and standards the html document conforms to and is crucial in evaluating the quality and technical validity of the html markup and css. Your web development technical team should be able to tell you which version of html will be used for page coding (for example, html4 or xhtml1) and which document type declaration will be used in your web site. html is the current basic standard for web page markup. xhtml is very similar to html, but xhtml is a subset of xml and has more exacting markup requirements. Although html is the most broadly used web markup standard, there are powerful advantages in using xhtml as your standard for page markup, including:

- Compatibility with xml techniques, xml content, and hybrid JavaScript/xml techniques such as Ajax

- Compatibility with non-html web markup standards such as Mathml for scientific documents, smil (Synchronized Multimedia Integration Language) for interactive audiovisual content, and Scalable Vector Graphics (svg)

- Future compatibility with newer xml content techniques, content management systems, and other evolving web technologies that will benefit from the greater consistency and structure of xhtml markup standards

Content markup

Semantic markup is a fancy term for common-sense html usage: if you write a headline, mark it with a heading tag (<h1>, <h2>). If you write basic paragraph text, place the text between paragraph tags (<p>…</p>). If you wish to emphasize an important phrase, mark it with strong emphasis (<strong>… </strong>). If you quote another writer, use the <blockquote> tag to signal that the text is a quotation. Never choose an html tag based on how it looks in a web browser. You can adjust the visual presentation of your content later with css to get the look you want for headlines, quotations, emphasized text, and other typography.

A few exclusively visual html tags such as <b> (boldface) and <i> (italics) persist in html because these visual styles are sometimes needed for other reasons, such as to italicize a scientific name (for example, Homo sapiens). If you use semantically meaningless tags like <b> or <i>, ask yourself whether a properly styled emphasis (<em>) or strong emphasis (<strong>) tag would convey more meaning.

html also contains semantic elements that are not visible to the reader but can be enormously useful behind the scenes with a team of site developers. Elements such as classes, ids, divisions, spans, and meta tags can make it easier for team members to understand, use, visually style, and programmatically control page elements. Many style sheet and programming techniques require careful semantic naming of page elements that will make your content more universally accessible and flexible.

Cascading Style Sheets

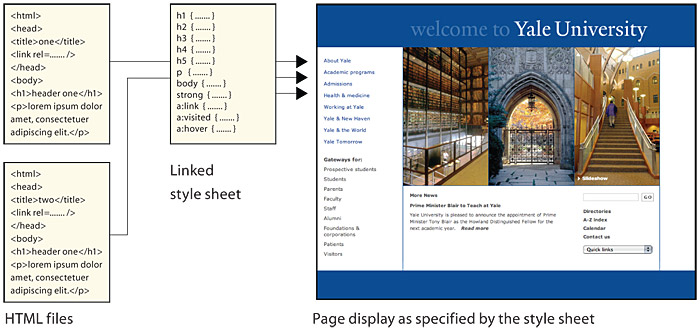

Cascading Style Sheets allow web publishers to retain the enormous benefits of using semantic html to convey logical document structure and meaning while giving graphic designers complete control over the visual display details of each html element. css works just like the style sheets in a word-processing program such as Microsoft Word. In Word, you can structure your document with ranked headlines and other styles and then globally change each one just by changing its style. css works the same way, particularly if you use linked external style sheets that every page in your web site shares. For example, if all of your pages link to the same master css file, you could change the font, size, and color of every <h1> heading in your site just by changing the <h1> style in your master style sheet (fig. 5.1).

Figure 5.1 — Style sheets translate HTML code into a particular layout for viewing, in this case for a full-sized computer screen. www.yale.edu

Audiovisual content

Web page files don’t contain graphics or audiovisual material directly but use image or other pointer links to incorporate graphics and media into the final assembly of the web page in the browser. These links, and the alternate text (“alt” text) or long description (“longdesc”) links they contain, are critical for universal usability and search engine visibility. Web users don’t just search for text. Search engines use the alternate text descriptions to label images with keywords, and visually impaired users depend on alternate text to describe the content of images. Proper semantic markup will ensure that your audiovisual media are maximally available to everyone in your audience and to search engines.

Interactive scripting

JavaScript is a language commonly used to create interactive behaviors. JavaScript is also a key technology in web page content delivery strategies such as Ajax. All JavaScript code belongs in the “head” area of your web page, but if your code is complex and lengthy, your “real” page content will be pushed dozens of lines down below the code and may not be found by search engines. If you use page-level JavaScript scripting (also called client-side scripting), you should place all but the shortest bits of code in a linked file. This way you can use lengthy, complex JavaScript without losing search page ranking.

Other document formats

The web supports document formats other than html. pdf (Portable Document Format), Flash, and Shockwave are formats commonly used to provide functionality that is not available using basic html. pdf files are favored for documents that originated in word-processing and page layout programs and retain the appearance of the original document. Flash and Shockwave provide interactivity beyond what is available using standard html. In general, the best approach is to offer documents as plain html because the markup offers greater flexibility and is designed to enable universal usability. At times, however, the additional features and functionality offered by these other formats is essential; in this case, be sure to use the software’s accessibility features. Adobe in particular has made efforts to incorporate accessibility features into its web formats by supporting semantic markup, text equivalents, and keyboard accessibility.

Watch for browser variations

html and css for tables, forms, positioning, and alignment sometimes work slightly differently in each brand or operating system version of web browser. These subtleties normally pass unnoticed, but in very precise or complex web page layouts they can lead to nasty surprises. Never trust the implementation of html, css, JavaScript, Java, or any plug-in architecture until you have seen your web pages displayed and working reliably with each major web browser and across operating platforms.

Check your web logs or use a service such as Google Analytics to be sure that you understand what browser brands, browser versions, and operating systems (Mac, Windows, mobile) are most common in your readership. If you encounter a discrepancy in how your pages render in different browsers, check that you are using valid html and css code (see chapter 1, html and css code validation). Not every browser supports every feature of css, particularly if that feature is seldom used or has recently been added to the official standards for css code. For example, although drop-shadowed text is a valid css option, not all browsers support it.

Summary on semantic markup

Set careful markup and editorial standards based on semantic markup techniques and standard html document types, and adhere to those standards throughout the development process. Today’s web environment is a lot more than just Internet Explorer or Firefox on a desktop computer—hundreds of mobile computing devices are now in use, and new ways of viewing and using web content are being invented every day. Ultimately, following semantic web markup practices and using carefully validated page code and style sheets is your best strategy for ensuring that your web content will be broadly useful and visible into the future.