Chapter 1

Strategy

You keep using that word, I do not think it means what you think it means.

—Inigo Montoya, The Princess Bride

We use the word “strategy” so widely and casually that it is worthwhile to step back and ask what exactly having a strategy for your web site project means, and why having one is so important.

Strategy is the art of sensible planning to marshal your resources toward their most efficient and effective use, over a significant period of time. A good strategy is flexible, and shows proper humility in the face of challenges. It does not pretend that miracles are possible or even desirable. It favors step-by-step progress toward your goals. A serious strategy does not depend on a lone “strategic thinker.” It acknowledges the major roles that chance and culture play in determining success. Great strategies are born from the efforts of small cohesive groups of people who are willing to be adaptive while never losing sight their primary goal.

A strategic approach takes time and effort, and the benefits are not immediately evident. Project success indicators, such as increased sales and subscriptions and happy customers, do not always map directly to elements found in a project strategy. The return on investment for project strategy becomes clear over time, through a well-executed project that produces a successful product, and is further evidenced by an ongoing attention and care to sustain that project and produce success over time.

Strategic Planning

Strategic planning is not a bag of tips, tricks, or special techniques. It’s not about predicting the future—we create strategies precisely because we can’t predict the future. Strategic planning is not a way to eliminate risk. At best, strategy is an attempt to identify and take the right risks at the right times.

Creating a strategic plan

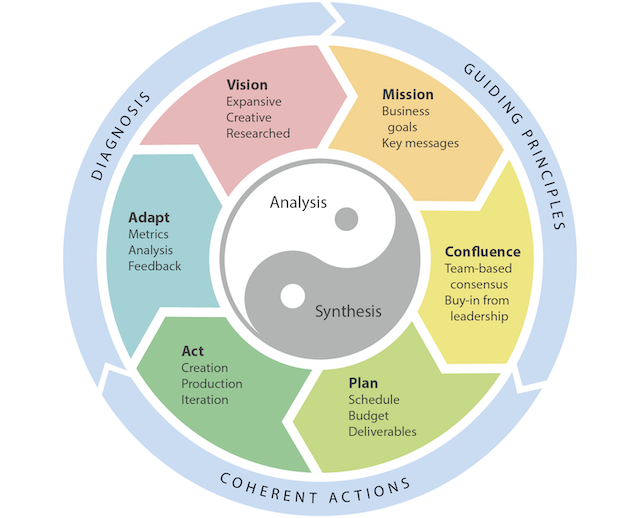

In his book Good Strategy/Bad Strategy management expert Richard Rumelt lays out a three-step process for creating a coherent strategy:

- Diagnose your situation

- Create guiding principles

- Design a set of coherent actions

Diagnose your situation

Identify your business goals, and let go of past practices and commitments. Strategy always starts with a vision of how to reach your business goals, and asks, “What do we have to do now to attain our objectives tomorrow?” Strategy starts with the facts as you establish them through research, diagnose the top few problems and needs to address immediately, and then form an overall plan of action.

- Be forward-looking: Strategy is inherently about the future. Don’t let planning discussions get bogged down in history and decisions that were made in the past. Keep the discussion focused on the future, defining what resources and tactics you will need to attain your goals.

- Stay focused on priorities: A good strategy doesn’t just create new things. It actively plans for decommissioning the old and outmoded, and pares away mediocre ideas and marginal priorities. If you can’t firmly articulate what business problem or user need your project will address, you can’t create a coherent strategy. Prioritizing is essential here, so don’t try to “boil the ocean” with an ambitious list of problems and needs. Your project can’t solve every known problem or user request. Prioritizing is hard. Too many projects fail because participants could not face the process of throwing out ten good ideas to focus on the top three or four great ideas or problems to solve.

Create guiding principles

Make every decision align with your road map. Every project plan is basically an answer to a series of questions: What do we need to do and when do we need to do it to step closer to our goals? There are no “short-term tactics.” Every decision and tactical work action today is a strategic move. Successful long-term projects are always built one strategic decision at a time, incrementally and iteratively moving the team forward toward purposeful work in support of business goals.

Design coherent actions

Consider your strategy a portfolio of options. Nobody has a crystal ball, so rationality demands flexibility. Insisting that business goals and deliverables must not change during a project is as absurd as insisting that we can perfectly predict the future. A good strategy is not a predetermined set of choices. It is a set of options that do not limit your tactical flexibility to respond to changing conditions. These options are often generated in advance by working through scenarios for how your project will respond to particular challenges that might arise and potentially change the budget, schedule, or deliverables of the project.

The truest test of any plan is whether it results in useful work on the correct tasks. Your strategy will succeed if it is rational, flexible and based on solid data and research, and if it takes advantage of the working knowledge of the team. But knowledge and a solid plan are not the goals—the successful product is the goal, and only smart work well executed with get you there.

Shaping the strategic plan

All too often, strategic planning activities never get any farther than a high-level vision statement. To put a plan into action, you first need to identify the people involved and their roles, then create a map to follow, through these processes:

- Define roles and responsibilities with project governance

- Adopt a user-centered approach

- Draw a strategic road map with a project charter

Evidence of clear priorities (or lack thereof)

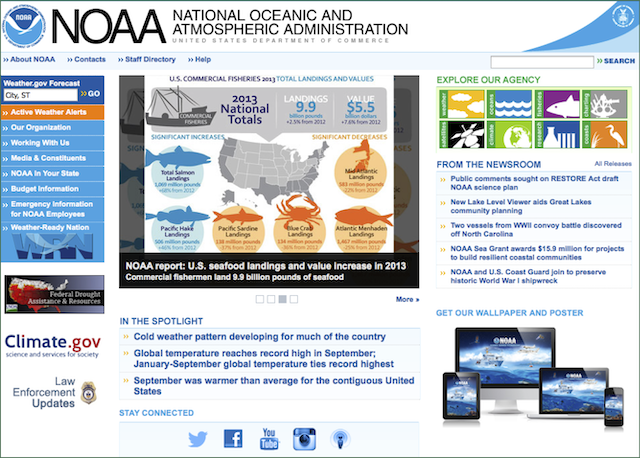

Often you can see an organization’s confusion about priorities simply by glancing at its home page or its product line.

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, Apple was selling sixteen to eighteen models of Macintosh computer. Jobs told an interviewer that even he couldn’t give clear advice to a friend on which Mac model she should buy for her home. Jobs’s first major strategic project was to cut the number of Macintosh models to four: two desktop computers and two laptops. Today the Macintosh product line still reflects this strategic focus on real user needs and a meaningful differentiation of products, and Apple is now the world’s most valuable company.

In contrast, designers of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s site seem to throw everything they can think of at their home page, and the resulting clutter and confusion reflects poorly on the excellent work that NOAA does in researching and monitoring the natural environment.

Define roles and responsibilities with project governance

Structure your team for a successful outcome. Most projects require collaboration within a project team and across the organization. You must clearly define goals from the start, and each person involved in the project must understand where she has authority to make decisions, and her accountability for the decisions she makes. Participants must also understand their responsibilities with respect to project activities. Additionally, they must understand roles and responsibilities of everyone on the project team, as well as those of the project sponsors. We can’t stress enough the importance of clearly defined project governance. Without it, projects can get bogged down, with team members working at cross-purposes, on activities that run counter to expectations from leadership.

To determine which governance model best suits your project, determine who has authority, responsibility, and accountability for different aspects of the project. Some aspects may involve multiple people; always identify one person who has primary responsibility. Some possible questions include:

- Who has the authority to initiate the project?

- Who has the authority to approve the design?

- Who is responsible for defining strategic direction for the project?

- Who is responsible for specifying the technology architecture?

- Who is responsible for assuring that the project is executed according to schedule?

- Who is responsible for the quality of the content?

- Who is responsible for coordinating site content?

- Who is responsible for creating content?

- Who is responsible for the day-to-day maintenance?

- Who is accountable if the project fails to meet stakeholder needs?

- Who is accountable if the project does not meet quality standards?

- Who is accountable for errors and misinformation?

Answers to questions such as these will help define who has decision-making roles, such as project sponsor, project lead, and product owner. The answers will clarify who is in development and production roles, such as technology lead and content editor. We cover these roles in more detail in Chapter 3, Process. The key in the strategic planning phase is to construct a solid governance model, and communicate roles and responsibilities to everyone who has a hand in the success of the project. Lisa Welchman’s book Managing Chaos is an excellent primer on strategy and governance in web and information technology.

Adopt a user-centered approach

Focus on user needs and perspectives. Web sites are developed by groups of people to meet the needs of other groups of people. Unfortunately, web projects are often approached as “technology problems,” and projects can get colored from the beginning by enthusiasms for particular web techniques (particular content management systems, responsive or adaptive designs, mobile-first design, web layout frameworks) rather than by human or business needs that emerge from engaging users in the development process. People are the key to successful web projects at every stage of development. Although the people who will visit and use your site will determine whether your project is a success, those users are the people least likely to be present and involved when your site is being designed and built. Remember that the site development team should always function as an active, committed advocate for the users and their needs.

Experienced committee warriors may be skeptical here: These are fine sentiments, but can you really do this in the face of management pressures, budget limitations, and divergent stakeholder interests? Well, yes, you can—because you have no other choice if your web project is to succeed. If you listen only to management directives, keep the process sealed tightly within your development team, and dictate to supposed users what the team imagines is best for them, be prepared for failure. Involve real users, listen and respond to what they say, test your designs with a spectrum of users of different ages, abilities, and interests, and be prepared to see your cherished ideas change and evolve in response to user feedback.

Draw a strategic road map with a project charter

Establish a common understanding of the path to desired outcomes. Successful projects begin with a high-level, shared understanding of goals and intent. The most critical requirement of this initial planning activity is to ensure all project participants are on the same page and working toward the same goals. A project charter document provides a conceptual framework and serves as a basis for decision making throughout the project life cycle. It consists of a project definition and high-level strategies for achieving project goals.

A project charter includes the following sections:

- Purpose: What purpose does the product serve?

- Goals: What outcomes does it need to achieve?

- Target audience: Whom must the product appeal to and work for?

- Success indicators: How will you know you have achieved project goals?

- Strategies: What approaches will help to realize the goals?

- Tactics: What activities might help to realize the strategies?

One of the best ways to ascertain the goals and objectives for a project is to envision what changes will occur if the project is successful. We often begin projects with a brainstorming exercise around indicators of success, asking the question “What changes will there be in the world if this project is successful?” The key in the exercise is not to get bogged down with questions like “Is that success indicator really measurable?” or “Can we really ascribe that change to this project?” By allowing free-flowing ideation and imagining you might come up with indicators like, for example, “happy customers” for a retail web site, or “better learning” for an open educational resource, or “healthier kids” for a game about children’s health. Stay with those, even though they are difficult to measure and correlate, because they tell you a great deal about purpose, objectives, and target audience.

The strategies and tactics section is where you begin to map out how you will go about realizing the project. A strategy is a general approach you might take to help you reach your goals. Each strategy has associated possible tactics—specific activities to support the strategy. The proposed tactics are tangible ideas for how you might implement content and functionality on your web site. For example, to produce the result of happy customers on a retail web site, one strategy should be to provide a user experience that is accessible and enjoyable for all visitors. Tactics for supporting that strategy would include following conventions for design and interaction, providing clear and consistent navigation, and testing usability with a wide range of users, including people with disabilities and older adults.

Share early drafts of the charter document with project stakeholders and the project team and invite changes and comments. Allow several editing cycles and be receptive about incorporating changes, remembering the importance of acceptance and support of the overall approach. Stay true to the format of the charter—make sure proposed tactics always support a strategy, which in turn serves a goal and supports the overall purpose.

Finalize the project charter before moving to the next phase of the project, with the understanding that the charter is a living document that may change over the project life cycle.

A sample project charter

The project charter is a concise statement of goals, values, and intent, and it drives the direction for everything that comes after. When you’re up to your neck in the daily challenges of building a site, it can be easy to forget why you are doing what you are doing and to lose sight of your original priorities, not knowing whether the decisions you are making firmly support the overall objectives. A well-written project charter is a powerful daily tool for judging the effectiveness of a development effort. It becomes a compass to keep the team firmly pointed at the goals established when you started the journey. A good project charter becomes a daily reference point for settling disputes, avoiding “scope creep,” judging the potential utility of new ideas as they arise, measuring progress, and keeping the development team focused on the end result. At the conclusion of a project, revisiting the charter can serve as confirmation that the design decisions made along the way were guided by strategy, and that the development team successfully met the project objectives.

Here we present the project definition portion of a project charter for a fictional app called Walk with Me, created by an outdoors equipment retailer that we will call Get Outdoors Equipment, or GOE. The app uses geolocation to track the route you are walking and collect photos and video, tagged with location details. The editor allows you to compile the route, media, and descriptive details into a trail guide to share with other Walk with Me users.

The purpose of the app is to create and share maps of favorite walks.

Get Outdoors Equipment provides the app for free. GOE is a retail company, but part of its core mission is to encourage outdoor activities for the purpose of promoting health and well-being. The company sees these activities as interdependent—a healthy customer base is more likely to purchase goods, and providing high-quality, affordable goods results in active and engaged customers.

GOE’s goals and objectives in creating Walk with Me are to:

- Sell outdoors equipment

- Create a community of people who value walking and nature

- Increase awareness of walks

- Add to general knowledge of available walks

- Get people outside and walking

GEO has a loyal customer base. That said, there are other outdoors equipment retailers that have strong offerings, and GEO must continually raise its efforts to keep its customers from changing brands. GEO knows that current customers are key to their continued success, since loyal customers repurchase and recommend—two key loyalty behaviors.

The target audience for Walk with Me is, in priority order:

- Current GEO customers

- Prospective GEO customers

- Walking and nature enthusiasts—who may become future customers

Measuring the success of the app is relatively straightforward, through downloads, account sign-ups, and contributions to the knowledge base. Indirect support makes it difficult to directly correlate the app with increased sales. However, it’s still worth monitoring, and certainly any direct links from the app to retail features should be closely tracked.

GEO can measure and monitor the following to use as indicators of success for the Walk with Me app:

- Downloads of the Walk with Me app

- Sign-ups for Walk with Me accounts

- Contributions to the Walk with Me knowledge base

- Sales, particularly for outdoors equipment related to walking

The next step is to build from the project definition strategies and tactics to support the project. For example, to support the goal of selling outdoors equipment, one strategy might be to provide an integrated experience between the Walk with Me app and the GEO retail web site. Tactics would include ensuring that the GEO retail web site experience is exceptional, then adding explicit links between the app and the web site.

Accessible User Experience

User experience, or UX, is a lens through which to view the whole range of site production tasks, from the earliest strategic planning and research to finished graphics. User experience incorporates all these things (at least in part), but the term really centers around core questions like How easy is a site to use? How memorable (even delightful) is a site? Is the site efficient? Most of all, did I get what I came to find? In short, the quality of user experience is measured by how usable and enjoyable a site is for people to use.

Core attributes of good UX include:

- Learnability: How quickly can first-time users learn what they need to know to find the information, services, or products they need from your site?

- Ease of orientation: Can users confidently and correctly judge their locations within your site’s navigation system?

- Efficiency: How quickly can users perform their browsing, searching, or other interactions to complete their tasks?

- Memorability: Can a user who has not visited for a long time quickly reestablish proficiency?

- Accessibility: Can users with physical or sensory challenges use the majority of your site’s content or services efficiently?

- Error forgiveness: Is your site forgiving of common user errors, and how often do users make errors in using your site?

- Delight: Do users typically enjoy using your site, or is it a chore?

The core user experience concepts of learnability, orientation, efficiency, and accessibility should influence every stage of site development, from the earliest concept sketches to site maintenance and continuous improvement.

Cultural context changes constantly: today there are few Internet “newbies” beyond preschool age, and there are now millions of adults who can’t remember a world before the web. Even in an age where smartphones, tablets, ultraportable laptops, and even smart watches and other digital “wearables” have vastly expanded the reach and use cases for web-based information, there is a timelessness about web user experience challenges. The range of devices we use to access the web has exploded, but neither the human nervous system nor the fundamental paradigms of browsing the web have changed that much in twenty-five years, and even lifelong users of the web will face challenges if your site is not well designed.

Today responding to the usability challenges of the web is more important than ever. Twenty years ago the web was a fascinating new toy, growing in usefulness, but mostly peripheral to our everyday life experiences. Ten years ago the web was optional: you might drop your newspaper subscription in favor of news sites, or shop on Amazon rather than do a tedious run to the shopping mall. Today the web is vital in everyday life: you may not be able to get health insurance, stay in contact with distant children, find medicines at an affordable price, or find your way home from an unfamiliar town without using the web.

Usability is a measure of quality and effectiveness. It describes how well tools and information sources help us accomplish tasks. The more usable the tool, the better able we are to achieve our goals. Many tools help us overcome physical limitations by making us stronger, faster, and more sharp-sighted. But tools can be frustrating or even disabling. When we encounter a tool that we cannot work with, either because it is poorly designed or because its design does not take into account our needs, we are limited in what we can accomplish.

In designing web sites our job is to reduce functional limitations through design. When we aim for universal usability, we improve the quality of life for more people more of the time. On the web, we can work toward universal usability by adopting a universal design approach to usability.

Human-computer interaction (HCI) pioneer Ben Shneiderman defines universal usability as “having more than 90% of all households as successful users of information and communications services at least once a week.” Note that Shneiderman is not just calling for any use of technology but is specifying successful use. He goes on to explain that, to achieve universal usability, designers need to “support a wide range of technologies, to accommodate diverse users, and to help users bridge the gap between what they know and what they need to know.”

Accessible user experience is informed by several initiatives, primarily accessibility, usability, and universal design.

Web accessibility: Since the World Wide Web Consortium established the Web Accessibility Initiative in 1999, the imperative of web accessibility has gained the attention of individuals, organizations, and governments worldwide. wai promotes best practices and tools that make the web accessible to people with disabilities. They also safeguard universal web access by providing expert input for development initiatives to ensure that accessible designs can be accomplished using current and future web technologies.

Web accessibility is a critical element of universal usability. The guidelines produced by wai and other accessibility initiatives provide us with techniques and specifications for how to create universally usable designs. They ensure that designers have the tools and technologies needed to create designs that work in different contexts. They provide a framework for evaluating digital products for accessibility, and identifying potential barriers.

Usability and user-centered design: Usability is both a qualitative measure of the experience of using a tool and a phenomenon that can be quantified as a concrete means to judge a design’s effectiveness. Quantitative usability metrics include how quickly we complete tasks and how many errors we make in the process. But usability can also be gauged by qualitative measures, such as how much satisfaction we derive in using a tool. “Learnability” is another important measure: how quickly we learn to use a tool and how well we remember how to use it the next time. Usability has an impact not only on our effectiveness but also on more fundamental qualities, such as loyalty. The more usable the tool, the better we feel about using it and, in the case of web sites, the more likely it is that we will return to the site.

The most common method for achieving usability is user-centered design (UCD). UCD includes user-oriented tools such as task analysis, focus groups, and usability testing to understand user needs and refine designs based on user feedback. UCD involves determining what functionality users want in a product and how they will use it. Through iterative cycles of design, testing, and refinement, UCD practitioners continuously check in to make sure they are on track—that users like the design and will be successful using it.

Universal usability arises from user-centered design, but with a broad and inclusive view of the user. UCD is applied to the task of designing web sites that are easy to learn and use by a diversity of users, platforms, and usage contexts.

Universal design: Universal design incorporates access requirements into a design, rather than providing alternate designs to meet specific needs, such as large print or Braille editions for vision-impaired readers. A common example of universal design in the built environment is the ramped entryway, which can be used by everyone and eliminates the need for a separate accessible entrance. Universal design has many benefits. A single design that meets broad needs is often less costly than multiple designs. And designs that anticipate a diverse user population often have unanticipated benefits. For example, curb cuts in sidewalks are intended to help mobility- and vision-impaired users, but many others benefit, including people making deliveries, pushing a stroller, or riding a bike.

Creating an accessible UX strategy

The first step toward the goal of universal usability is to discard the notion that we are designing for a “typical” user. Universal usability accounts for users of all ages, experience levels, and physical or sensory limitations. Users also vary widely in their technical circumstances: in screen size, network speed, browser versions, and specialized software, such as screen readers for the visually impaired. Each of us inhabits multiple points on the spectrum, points that are constantly shifting as our needs and contexts change. For example, virtually all adults over fifty have some form of mild to moderate visual impairment. And within that context our needs change as we move from viewing web pages from the back of an auditorium to sitting in front of a large desktop display monitor to walking down the street peering at a small mobile display. A broad user definition that includes the full range of user needs and contexts is the first step in producing universally usable designs.

Next we need a design approach that will accommodate the diversity of our user base, and here we turn to the principle of adaptation. On the web, universal usability is achieved through adaptive design, where documents transform to accommodate different user needs and contexts. Adaptive design is the means by which we support a wide range of technologies and diverse users. The following guidelines support adaptation.

Flexibility: Universal usability is difficult to achieve in a physical environment, where certain parameters are necessarily “locked in.” It would be difficult to make a book, and a chair to read it in, that fit the needs and preferences of every reader. The digital environment is another story. Digital documents can adapt to different access devices and user needs based on the requirements of the context.

A web page contains text, with pointers to other types of documents, such as images and video. Software reads the page and acts on it by, for example, displaying the page visually in the browser. But because of the nature of the web, the same page can be accessed on a smartphone, using a screen reader, or printed on paper. The success of this adaptation depends on whether the design supports flexibility. Pages designed exclusively for large displays will not display well on the small screens of cell phones.

The web environment is flexible, with source documents that adapt to different contexts. When considering universal usability, we need to anticipate diversity and build flexible pages that adapt gracefully to a wide variety of displays and user needs.

User control: In many design fields, designers make choices that give shape to a thing, and these choices, particularly in a fixed environment, are bound to exclude some users. No one text size will be readable by all readers, but the book designer must make a decision about what size to set text, and that decision is likely to produce text that is too small for some readers. In the web environment, users have control over their environment. For example, users can manipulate browser settings to display text at a size that they find comfortable for reading.

Flexibility paired with user control allows users to shape their web experience into a form that works within their use context.

Keyboard functionality: Universal usability is not just about access to information. Another crucial component is interaction, which allows users to navigate and interact with links, forms, and other elements of the web interface. For universal usability, these actionable elements must be workable from the keyboard. Many users cannot work with a mouse, and many devices do not support point-and-click interaction. For example, nonvisual users cannot see the screen. Some users employ software or other input devices that work only by activating keyboard commands. For these users, elements that can be activated only with a mouse are inaccessible.

Make actionable elements workable via the keyboard to ensure that the interactivity of the web is accessible to the broadest spectrum of users.

Text equivalents: Text is universally accessible. (Whether text is universally comprehensible is another discussion!) Unlike images and media, text is readable by software and can be rendered in different formats and acted upon by software. When information is presented in a format other than text, such as visually using images or video or audibly using speech, the information can be lost on users who cannot see or hear. Web technology anticipates format-related access issues and supplies methods for providing equivalent text. With equivalent text, the information contained in the media is also available as text, such as a text transcript or captions along with spoken audio.

Text equivalents allow universal usability to exist in a media-rich environment by carrying information to users who cannot access information in a given format.

Content Strategy

Content strategy governs and defines how the content you develop will meet your business goals. To experienced writers and editors, most of “content strategy” will seem the “same as it ever was” for complex publications. Editorial work has always been concerned with the purpose, form, development, and integration of all kinds of content assets: text, illustrations, and, for the past few decades, interactive and audiovisual materials that are integrated into electronic publications.

However, content development today has to contend with additional layers of complexity. Presentation media for content range from traditional paper and web publications to mobile applications that appear on an increasingly wide spectrum of screen sizes and different contexts for use. This flexibility in the various ways content might be deployed requires much more structure, modularity, and metadata than print-only publications.

It might be best to think of modern content as the elements of a database, in which sections, chapters, descriptions, and even individual paragraphs of text might be remixed and displayed in myriad ways for print, web, applications and apps, and social media. Content strategy seeks the flexibility to move beyond a single medium and a single fixed presentation narrative so that your content can work effectively across the breadth of your communications channels. Today content also needs to be as visible as possible to search engines, and also accessible to all audiences.

In this new multichannel media universe a comprehensive content strategy produces a road map to guide the whole content life cycle, from needs assessments and business strategy alignment to development, deployment, and revision or deletion. Content development is not a project, it’s an ongoing process, and it is never “done” until the site goes offline and is archived. A good content strategy explicitly acknowledges that today’s shiny new site or app will one day seem painfully dated, and that content begins to drift out of date from the moment it goes “live” online. As content strategist Karen McGrane says, “It’s not a strategy if you can’t maintain it.”

A good content strategy also looks both backward and forward, working with site managers to create and measure benchmarks and performance metrics—gauging the success of your content and assessing its current strengths and weaknesses at meeting the needs of your audience—and uses those metrics to establish priorities for fixing, revising, or updating areas of content.

Creating a content strategy

The goal of a content strategy is not editorial work or content creation, although in many cases the same people will be involved in both creating a content strategy and implementing the strategy recommendations. The key result, or “deliverable,” is a content strategy document that details all of the elements described below, with recommendations for resources, workflows, and editorial team members and their roles and responsibilities, while incorporating guidance or style documents that describe the voice and tone, content structure, content templates, and other guides for content contributors like writers, photographers, graphics artists, and audiovisual media creators.

Content strategy is more broad in scope than most conventional web editorial processes; it includes business goals and branding processes, and covers the whole content life cycle, not just the creation and deployment of content. It also deals with the more technical aspects of digital content, such as content structure, metadata, file formats, search engine optimization (SEO), and the accessibility of content across various delivery media.

Define your target audience

It is impossible to develop a coherent content strategy without clear ideas about whom you are speaking to, what their needs and interests are, and how those needs might be met by your content. Audiences are rarely homogeneous, and you’ll need to identify primary audiences as well as possible subgroups within your audience that might need slightly different information and marketing messages, or a different voice and tone in your presentations.

- Prioritize audiences: Not all possible audiences are equally important to your business goals. One of the key processes in identifying your audiences is to prioritize the various groups of readers and users so that your messaging strategy and mix of media (web, apps, social, print) are carefully targeted at your most important audience. This is not to say that secondary audiences are not important. If your site’s primary audience is prospective customers, you must also support existing customers, even if your primary business goal is increased sales, because poor support will eventually damage your sales and reputation.

- Develop personas: User interface professionals often develop detailed audience personas—individualized portraits of representative audience members (see Chapter 2, Research), usually fashioned around some particular interest or audience demographic. For content strategy, it helps to understand the major characteristics and interests of each audience group as a reference for prioritizing your messaging, so that your writers and designers thoroughly understand whom they are speaking to when creating content.

Articulate key messages and business value

Messaging is the process of prioritizing and matching your key business strategy messages with particular audience segments. This is impossible without a clear understanding of your business goals, and every piece of content you develop should have a direct relationship to business goals, or a key message to your audience. If you are lucky, your enterprise may already have a clearly articulated business strategy and well-established marketing or communications messages, and your project should support those goals. If not, one of the most important aspects of content strategy will be to develop a concise statement of business purposes and key desired outcomes for each audience type, so that each key message has a clear “job” to do to support your overall goals.

The concept of “messaging” might seem nebulous on a relatively small department site, but the same principles apply whether you are developing the web site for a large enterprise or a help desk site for the enterprise’s it department. For a help desk your key messages might be that your site provides fast, accurate, and user-friendly access to the technical information your users need to get their jobs done. Each piece of content should reflect these high-level goals for effective and usable support information and services. Technically obtuse, bloated, or inaccurate content is not compatible with your key messaging. Whoever is developing your content needs to keep the high-level goals in mind for each sentence and paragraph, as the overall “message” of your site is built from the aggregate impressions given by every piece of content your audience encounters.

Choose your distribution media

One of the principal advantages of digital content is the ability to deploy the same material over a wide variety of communications channels, but this potential flexibility is available only if you plan for it carefully and ensure that your content is well suited in messaging, tone, and technical structure for each potential use. In the parlance of marketing, each communication medium is a “channel,” and each medium could have multiple channels. For example, your internal enterprise intranet and your latest marketing campaign site may both be web-based, but they are different channels with different audiences and goals.

Corporate web sites, blogs, the various social media that your company uses, mobile applications, online video sites like YouTube, podcasts, magazine and newspaper advertising, marketing publications in print and pdf, and television advertisements are all potential “channels” for matching your key messages to your target audiences. Not every medium is equally suitable to your business purposes, and unless you are working for a large enterprise, you may be able to support content in only a few of the available media channels. Content strategy for distribution is the process of identifying and prioritizing the most effective channels for your messages, and creating a plan that specifies the content character, structure, and tone for each medium.

Specify the content structure

Once you know which communications channels you will support, you need to be sure that the content that you create, curate, or license is structured to meet your needs for each channel. “Content structure” in this case is only partly related to conventional editorial structures like titles, chapters, subheads, paragraphs, and figure references. The goal for strategic content structuring is to anticipate the unique needs of each known communication channel, and to be sure that the content you develop or repurpose is organized in an optimal way for many different potential uses.

Detailed specifications for content structure also bring consistency and modularity to the development of large amounts of content, which often combines the work of many writers and designers.

Provide voice, tone, and editorial guidance

In daily life we all adjust our tone of voice and manner of speaking to the context we’re in: informal and matter-of-fact among friends, still informal but more careful in routine emails with office mates, and more formal when writing a company white paper on an aspect of business strategy. Although most enterprises have established editorial and graphics guides for general corporate identity, they rarely are up to date enough to include guidance on social media and other newer communications channels. What sounds perfectly appropriate for business-to-business communication or a LinkedIn article might sound oddly stilted in a tweet or a Facebook post.

Content strategy looks at each communication channel and provides general guidance on the voice and tone of communications for that channel and its audience. Guidelines for each medium and each audience will help your writers and other contributors develop content that “sounds right” for the intended communications channel (see Chapter 10, Editorial Style).

A good content strategy will include at least general recommendations for editorial style, particularly if organizational standards, identity guidelines, and language style guides do not already exist.

Create an editorial workflow

A good content strategy looks at available editorial resources and existing content in light of stated business goals for your project, and develops specific recommendations and workflows for the staff, media, and editorial resources need to successfully meet your goals and production schedule.

Many editorial tasks are predictable, and a good strategy will spell out roles and responsibilities for each task, how handoff and approvals will occur, typical workflows for each type of content (text, photos, graphics, etc.), and who has the final authority to publish the finished content. Common editorial tasks include:

- Planning

- Creating content inventories (see Chapter 10, Editorial Style)

- Maintaining the editorial calendar

- Creating or sourcing content

- Editing and revising content and the expected workflow

- Adding metadata and checking for accessibility issues

- Testing the content as it is integrated into a working version of the web site

- Getting final approvals from editors, stakeholders and marketing staff, and legal

- Getting technical approvals for highly programmed or interactive content

- Getting clarity on who has the authority to publish content, and how that final workflow will occur

- Reviewing current “live” content for editorial quality and proper functioning

- Receiving and responding to reader feedback, requests for information, or reports of problems

- Determining how error reports will be handled, ideally in a ticketing system to track and prioritize known problems

- Removing outdated or incorrect content, with clarity on who has the authority to remove content from the “live” site, and how that workflow will occur

Most content strategies recommend the development (or continued use of) an editorial calendar. If the project is new and doesn’t have an established calendar, it’s good to be clear on exactly what you hope to accomplish with an editorial calendar, and how it will be used to record key dates for product announcements, events, recurring annual events, product rollouts. It should be clear who maintains the editorial calendar, and whose responsibility it is to develop and post content for each event.

Stipulate governance and the content life cycle

Many web sites are considered to be projects that are “finished” at site launch, and then often languish with increasingly outdated content, broken links, and eroding interactive functionality, principally because the site never had a clear governance structure beyond the launch date. Content strategy and web governance are tightly related because only through governance can the content life cycle be maintained with high quality and functionality (see “Define roles and responsibilities with project governance,” above).

Governance for content strategy specifies roles and responsibilities related to content, from conception, creation, and launch to eventual revision or removal. Ongoing support is usually the most crucial element, as it is only with continued support that content will be maintained. A content governance model assures:

- Clear communication among the site editorial staff, site stakeholders, and management.

- Established roles, responsibilities, and ongoing support for editorial staff, clarifying who supplies subject matter expertise for each content area as technologies and circumstances change over time.

- Communication between major stakeholders and the editorial staff on the overall business success of the site: Is the content supporting the original or evolving business goals, and at what point will substantial changes need to be planned?

A mobile-first approach to content strategy

The rapid and widespread development of mobile computing may be the best thing that ever happened to desktop computing, because once companies understood how many mobile-first and “mobile-often” customers there are out there—more every day—they realized that foisting a stripped-down, dumbed-down version of their content on mobile users just wouldn’t work. It’s far too expensive and complicated to maintain several versions of your large site or e-commerce store. Yet mobile screens are so small. What to do?

Cut, cut, cut. Cut all the bloated, irrelevant verbiage, “features” your user data say that no one ever touches, giant photos and graphics nobody bothered to optimize for fast download, useless wads of CSS code from three versions ago that everyone is afraid to touch (is it still live somewhere?). In short, the severe restrictions on what will work well in the mobile context, as well as the concise content approach required for mobile content, are also wonderful in desktop situations. A well-executed mobile content strategy can result in lean, focused, high-priority content across all of your mobile and desktop audiences.

There’s no such thing as “mobile content.” What all your readers and users need is good content, available wherever and whenever they need it, on any device. If some of your current content looks superfluous on a mobile device, it’s certainly superfluous for desktop users as well. Get rid of the useless fluff—it makes everyone’s day harder, and it’s expensive to maintain. Prioritizing your content is essential, but don’t dumb down your content for mobile users. Make all of your content concise and highly informative. Both desktop and mobile users will thank you for it.

Simplicity is a must. In content strategy and user experience the “mobile-first” design philosophy makes a great heuristic for cutting away the crap and getting down to essential content and features—for all users, across all devices.

Social Media Strategy

As the infrastructure of the web has become bigger, more complex, and richer with communications possibilities, the web is now much more than the content of individual web sites and blogs. For most individuals—and a growing list of major enterprises—their presence on various social media channels has at least as much impact on audiences as their corporate sites or enterprise blogs.

Social media are often reviled as playgrounds for the trivial, but they finally accomplished what no previous Internet technology had successfully done before: they brought masses of ordinary people onto the web, with all their foolishness, trolls, flame wars, wisdom, connection, and deep humanity.

Creating a social media strategy

After an initial few years of diffidence, businesses and other enterprises have long since adopted social media technology because of the unprecedented forum it provides for easy, fast interactive communication, bringing with it far more opportunity than the older one-way media channels of television, print, and static web sites.

However, social media channels also pose new challenges to marketing, branding, and communications professionals. Strategy and tactics in social media need to be flexible, ready to change quickly as conditions, practices, and expectations change. New functionality—and even whole new social media channels—emerge almost weekly, and channels like Facebook and Twitter change their policies and technology frequently. One thing doesn’t change, though: a quality enterprise social media presence is expensive and requires careful attention from both experienced communications professionals and senior management. Without clear goals and solid business objectives your social media efforts will wander, and may reflect poorly on your reputation.

Define business objectives

Do you have clear understanding and agreement on what are you trying to accomplish through using social media? What key performance indicators (KPIs) are most important to you and your overall enterprise business strategy? A good social media strategy should always begin with your enterprise-wide goals, and clearly work to support those goals.

Social media can help:

- Develop new customers, clients, or community members

- Increase sales or other forms of engagement with your current customer community

- Broaden and deepen your brand’s reputation

- Provide customer support and useful product information

Define your audience

Are you clear on who your most important social media audiences are, what you have to say to them, and what information or services are most important to audience members? Social media interactions play out in real time: do you know what most interests your potential audiences, and at what times of day are your audiences most active and engaged?

Learn about your target audience, including:

- Gender, age group, or interests

- Level of education or professional interests

- Geographic locations, time zones, and languages spoken

- Social media channels preferred

Most large enterprises have one “main” account for each major social medium like Facebook or Twitter but also maintain other accounts targeted at more specific audiences. For example, Yale University maintains a primary institutional Twitter account but also maintains dozens of other Twitter accounts from more specialized sources, like academic departments and programs, as well as Twitter accounts aimed primarily (but not exclusively) at on-campus audiences. A coordinated approach to enterprise social media is an ideal way to extend the reach of more specialized content (through retweets to the general audience), but the general audience for the main enterprise feed also benefits from a wide variety of content of more specialized topical posts.

Project—and protect—your brand and enterprise identity

Social media can be powerful tools for projecting your business brand or enterprise identity, but only if you plan carefully, and provide enough of the right resources to solidify and enlarge your reputation through daily interactions with your audience members. Your social media efforts should always be consistent in tone and design with your existing enterprise identity guidelines and policies.

Expand your branding guidelines to include provisions for social media, including:

- Visual branding: Each social medium has its unique graphic formats and pixel dimensions for themes, background images, header and profile images, and ideal image formats for visual posts. You’ll need to consult (and probably update) your standard enterprise identity guidelines for each social media channel to be sure you have the best-quality brand images.

- Video titling standards: The most effective online videos are short—ideally no more than two to three minutes long—and relatively lengthy “cinema style” beginning and ending video graphics are counterproductive for channels like Facebook, YouTube, or Vimeo. Online audiences won’t sit through fifteen seconds of fancy titles to see whether your video is interesting. You’ll need to give your video “fast-start” titles that appear over content that starts to play immediately (see Chapter 12, Video).

- Voice and tone: Traditional print or broadcast branding guidelines rarely provide useful counsel for deeply interactive social media channels, where the usually conservative editorial guidelines may prove to be too neutral in tone for the relatively informal conversational style of social media channels like Facebook and Twitter. Developing the right editorial “voice” will depend heavily on the characteristics of your particular audience demographics, and which channels you are using. Facebook tends to be relatively informal, whereas the more business-oriented LinkedIn audience will expect a more neutral “corporate” voice.

- Integration with existing online branding: Most enterprises have long since developed policies for web site and blog identities and graphics, but may neglect to thoroughly integrate social media into existing web sites, blogs, and mobile content efforts such as smartphone or tablet apps. Linking your social media efforts to your existing web communications through “like” and “share” buttons is a crucial piece of a mature social media strategy, and cross-linking your web site by embedding your latest social media posts can help boost audience traffic to both your web site and your social media efforts.

- Response policy: Participating on social media channels opens enterprises to possible reputational risk. For example, enabling a commenting feature on articles invites contributions from readers, and those comments may not always be complimentary. Some implementations may invite more risk than others—for example, allowing anonymous posts may lead to more “trolls” using the comments feature to shout contrary viewpoints. Any social media strategy must have a plan for how to respond to negative and potentially harmful engagement on social media channels. The policy should take into account the risks of moderation as well—how will your brand stand up to claims of censorship? Create a “code of conduct” that encapsulates your enterprise’s core values, post the code on your social media channels, and ensure that all staff who engage in social media channels know how to respond to violations.

Produce compelling content

What information will you share with social media audience members? If you sell goods, you might share information about your products and how they are used, as well as success stories from customers. Local governments and universities might share information on local events and programs, interesting people, current research, and publications. Social media are also ideal for projecting a sense of place, and for giving distant audiences (prospective students or potential new businesses, for example) a taste of what it is like to live, work, or study in your local environment. Each social media channel requires a tailored mix of media best suited to that audience’s expectations, but in general highly visual content like photos and video does best, and content that provokes positive discussion and reader feedback will both increase your engagement with individual readers and boost the overall visibility of your social media content.

Content curation—selecting and sharing social content produced outside your enterprise—has become a crucial component of most enterprise social media strategies, as it helps provide a rich mix of content well beyond the content you produce yourselves. Your audience members are not interested just in your home-grown communications; they usually want to know what you find interesting enough to retweet or repost among relevant industry news, graphics and videos, or comments produced by others.

Whom to “follow” on Twitter or Facebook has become a subbranch of content curation, as a “follow” list from your Twitter account is a powerful statement of which corporate sources, news outlets, and individuals you find interesting and relevant enough to pay attention to.

Determine optimal timing and frequency of posts

Two general characteristics of social media channels can be useful in creating your strategy: the ideal posting frequency of the medium, and the general level of posting “noise” typical of each medium. For example, it is rare for large enterprises to post more than four or five times per day on Facebook, and posts on LinkedIn are even less frequent. Audiences will quickly come to resent too many posts from a business, as both Facebook and LinkedIn are communities of individuals who have chosen to associate with one another. Too many commercial posts mixed in with their usual news from friends and family will cause users to “unfriend” or “unfollow” a business.

In contrast, Twitter is a completely open social medium, where almost all tweets are inherently public, and where many tweets from a wide variety of sources may swamp your message amid the general noise of the typical user’s Twitter feed. Twitter postings (“tweets”) are ephemeral, so most organizations post multiple times per day to assure that the average follower sees some piece of content per day. Studies show that the “half-life” of a tweet (50 percent of all retweets) occurs within eighteen minutes. Still, an enterprise should normally post no more than once an hour (and usually much less), as even Twitter users will quickly resent a company that seems to be monopolizing their feed with too many tweets.

All social posts have relatively short lifespans, ranging from as brief as the eighteen-minute half-life of a Twitter post to several hours for most Facebook posts, and perhaps days for less frequently visited sites such as LinkedIn.

Many studies have looked at the optimal times to post in the major social media channels, but only one rule ultimately matters for your situation: Use data from your audience to tailor the timing of your posts. Use the metrics available in Facebook and Twitter, make careful notes on which of your posts get the most engagement and when they get it, and tailor your posting schedule to your particular audience. If you have a nationwide U.S. audience, you’ll need to account for the various time zones in the country, and also determine the best times to post for international readers in Europe or Asian markets.

That said, there are consistent trends in the way people typically interact with the major social media channels. In general, for Facebook and Twitter (more than 90 percent of current social media traffic), weekday midafternoons and early evenings (measured in Eastern Standard Time, est) are best for engagement on Facebook postings, and Twitter users are most likely to engage with a tweet in a broader range of the day, from late morning through early evening. The late-day est bias for Facebook and Twitter engagement is probably influenced by the various U.S. time zones, because it is still early afternoon for midwestern and West Coast readers while East Coast readers are in late afternoon or early evening.

Both Facebook and Twitter show more engagement early in the workweek. Weekends tend to be quiet times for business uses of Facebook and Twitter, but business posts aimed at personal users may see higher levels of engagement on Sunday, mostly because so few businesses post on weekends, so the few that appear on Sunday are more prominent.

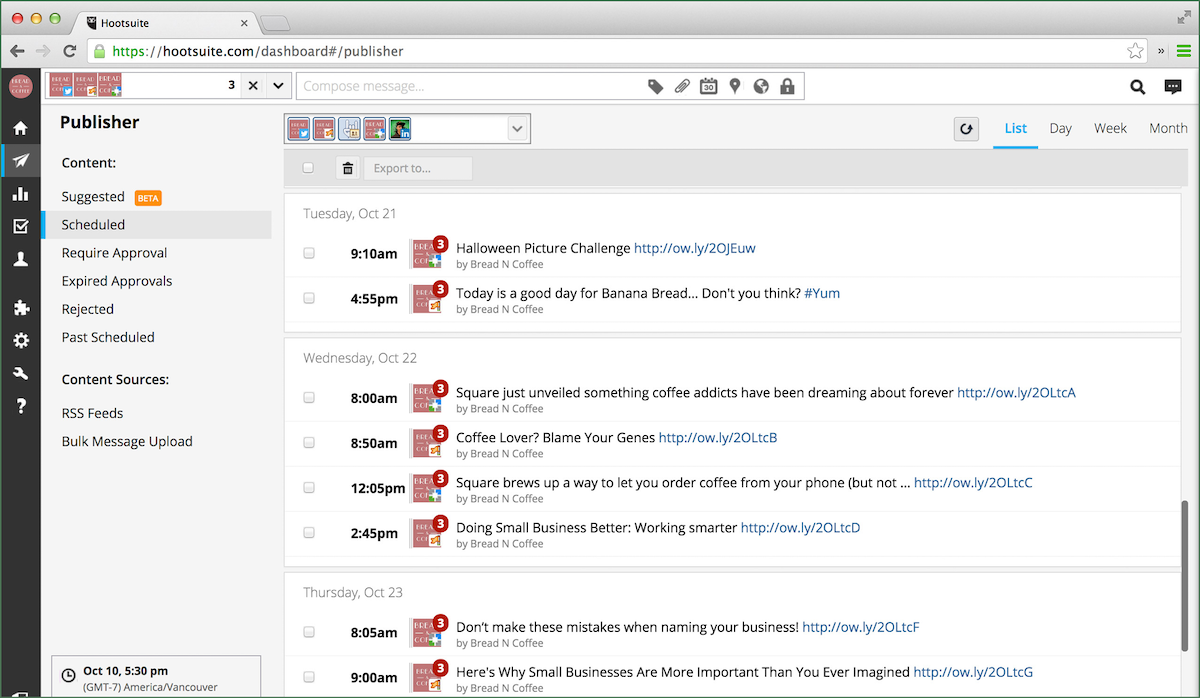

Organize and schedule social media activities

Social media are inherently immediate, but that does not mean that it is a good idea—or even practical—to produce all of your social media posts in real time. Popular social media organizing and scheduling tools like Hootsuite, Buffer, and Sprout Social allow you to schedule sets of social media posts for all the major social media channels at various dates and times, often far in advance. Multiple users can see, edit, and coordinate content campaigns across a variety of media and a variety of individual accounts in a single place, which makes for much more coherent and strategic social media content.

A list of reminders

—With apologies to E. B. White

Place yourself in the background. Start and end with the users’ interests in mind. If your site doesn’t provide useful things to the audience, nothing else matters. Design your web site using universal usability principles.

Work from a suitable design. Avoid the perils of the “ready, fire, aim” syndrome. The crucial part of the project is the planning. Know what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, and for whom you’re doing it before anyone touches HTML or CSS.

Do not overwrite. Small is good. A concise, high-quality site is much better than a big contraption full of broken links. Produce the minimum necessary to achieve an excellent result.

Prefer the standard to the offbeat. Web conventions are your friends. Always favor the tried and true, and save your creativity for the hard stuff: interesting content and features.

Be clear. Craft your page titles and content carefully, and make sure that the page title is consistent with your major headings.

Do the visuals last. Early visual design discussions can ruin any chance of a rational planning process. Louis Sullivan was right: form follows function.

Revise and rewrite. Design iteration in the early stages of the project is good. In planning, keep the team open to new ideas, feedback from existing and potential users, and the interests of your project stakeholders. However, development iteration—where you tear down and revise things late in the process—can ruin quality control, budgets, and schedules.

Be consistent. Consistency is the golden rule of interface design. Be consistent with the general conventions of the web, of your home institution if you have one, and within your site.

Do not affect a breezy manner. Avoid gimmicky technology fads. “We should use Sass” is not a technology strategy, unless you know exactly why and how Sass with CSS might help you to achieve your strategic goals. Never use pointless CSS or GIF animations to “make the site more interesting.” To make your site more interesting, add substantive content or features.

Degrade gracefully. Apply universal usability principles in your site development and careful quality controls in your web applications. Provide a carefully designed “404” error page with helpful search and links in case the user hits a broken link on your site.

Do not explain too much. Be concise, and be generous with headers, subheads, and lists, so that the user can scan your content easily.

Make sure the user knows who is speaking. Good communication is always a person-to-person transaction. Use the active voice at all times, so the user knows who is speaking. Make it easy to find your mailing address and other contact information.

Reaching your audience through social media channels

What social media channels will you use—Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr, Google+, YouTube, blogs? Each of the major social media channels has unique characteristics. With limited resources you’ll want to choose just a few channels that best suit your business objectives, and determine what level of engagement best suits your resources and strategy. Facebook (more than 80 percent of users) and Twitter (roughly 20 percent of users) account for more than 90 percent of adult time spent on social media in the United States. While we concentrate on Facebook and Twitter in this chapter, the strategy, design, and staffing considerations also apply to other widely used social media channels like LinkedIn, YouTube, Tumblr, and Instagram.

Facebook is a business whose primary product is access to the enormous international community of Facebook users. More than a billion worldwide users, or about one in thirteen people on earth. In the United States more than 80 percent of time spent on social media sites is on Facebook.

If you are a business or personal user of Facebook, then every content posting you make on the medium will appear on your Facebook Timeline page. However, 90 percent of Facebook users who “like” or “follow” your Timeline page on Facebook will never revisit your Timeline page, and will see your content only on their personal Facebook News Feed. Facebook’s News Feed filtering algorithms (previously called the EdgeRank algorithm—see “Facebook Ranking Algorithms” sidebar) determine how often users see the content you post to Facebook.

New users of Facebook are often unpleasantly surprised to discover that relatively few posts they make on Facebook make it into the News Feed of every person who has “friended,” “liked,” or “followed” a commercial or personal Facebook page. Facebook has long used a variety of techniques to filter the sheer volume of daily posts, both to better tailor content for individual Facebook users and to help steer commercial users of Facebook toward the company’s paid services to boost viewership of postings. The result is that only about 6–16 percent of posts reach the News Feeds of people who have liked their pages, and some industry experts find that organic reach has fallen to as little as 2–3 percent for some commercial Facebook users. Facebook says that average “organic reach” of about 6–16 percent is typical of both individual Facebook users and commercial or brand pages. If you want to reach more of the audience that has liked or followed your page, you must use one or both of these basic Facebook content strategies:

- Create compelling content tailored to the specific characteristics of Facebook as a social medium.

- Pay Facebook to “sponsor” or “boost” the percentage of users who see your posts.

Through careful Facebook-specific design of your content, it is possible to increase the ranking your posts receive, thereby increasing the total organic reach of your posts and the visibility of your content.

- Engaging content: Posts with photos, illustrations, or videos get more reader engagement. Carefully determine your target audiences, and create highly visual content with concise text captions of no more than about 150 characters. Try to provide unique content in your Facebook feed, with Facebook-first news and information, sneak-peek information on upcoming announcements and sales, or useful product tips.

- Posting frequency: In previous years most experts advised commercial companies not to post more than once or twice per day to avoid annoying their audience. The current News Feed system severely limits the organic reach of your posts, so many organizations have begun to send two or three posts per day, with the assumption that most Facebook users may see only one or two of those posts in their News Feeds. Many brands post no more than once a day (five or six times per week).

- Post timing and maintaining a calendar: There are general rules for the timing of social media posts, but the only metric that really matters is the best timing for your particular audience. Use your page metrics to pay close attention to the timing of your most successful posts, and adjust your timing accordingly. Use a detailed calendar to plan your social media campaigns, both to assure that your lessons learned are applied systematically and to be sure that everyone on the social media team understands the daily and weekly strategy for content and post timing.

- Interactions with fans: Your overall News Feed scores and your organic reach will rise with the degree to which you engage with readers who comment on your Facebook posts. Two-way conversations help build customer loyalty and assure your audience that there is somebody listening to and thinking about comments, suggestions, and complaints.

Most of us already use Facebook in our personal lives, and it may appear odd to discuss the components of something that seems so familiar, but professional uses of Facebook are costly and far from casual, and you’ll want to be sure to create the most effective posts you can to increase your audience reach and engagement.

- Length: Keep the copy in your Facebook posts short, ideally no more than 100 characters. Facebook does not carry the strict 140-character limit of Twitter, but that doesn’t mean that you can ramble. Only the first two or three sentences are visible in a Facebook post anyway before Facebook cuts off the rest of the text with a “See More” link. Be concise: Facebook posts of 80 characters or fewer receive 66 percent higher engagement from readers.

- Photography and graphics: This is simple: If you want people to pay attention to what you say on Facebook, always include a graphic in your posts. Facebook is a highly visual medium, and posts with graphics consistently outperform text-only posts. A recent study found that graphic posts generate 53 percent more reader engagement than text posts. The graphics do not need to be large. Facebook typically displays News Feed graphics in a 4:3 horizontal rectangle in jpeg format, and the graphic needs to be no larger than 504 pixels wide to fill the full width of the News Feed or the timeline. If you have photos or graphics that will benefit from the extra resolution when a reader clicks on the photo, do use a larger jpeg, but there is little point in uploading graphics larger than about 1,300 pixels in width, as Facebook will scale down large graphics, and most users won’t have enough screen real estate to view very large photos within the Facebook page framework anyway.

- Hashtags: Hashtags are a relatively new feature of Facebook, but although they are not yet widely used, they function the same way they do in Twitter, providing a searchable tag that allows readers to see collections of posts that all reference the same hashtag. Facebook hashtags are now used mostly by television companies to identify posts about sports and news events, but it is likely that usage will grow as Facebook users become more familiar with them.

Twitter has more than 271 million active monthly users and is often reported to be the fastest-growing social network. For the average user Twitter is a very cluttered and fast-changing medium, where dozens of tweets per hour flow through the feed. Given such a volume of information, few users attempt to “drink from the fire hose”—try to pay attention to every tweet. Twitter is a noisy medium where older tweets are quickly forgotten by most users, if they are ever seen at all. The average active Twitter user follows 102 accounts, resulting in an average active lifespan per tweet of less than half an hour before retweets and comments fall to near zero.

The immediacy of Twitter lends itself to commenting “real time” on news and entertainment events as they unfold. Twitter is commonly used by journalists and news organizations to break and follow news, and is often the first (if not the most reliable) source for major news events.

Twitter recommends that commercial accounts tweet three to five times per day. Twitter postings (“tweets”) are famously brief, at no more than 140 characters. However, there are best practices for writing, forming, tagging, and adding media links to tweets.

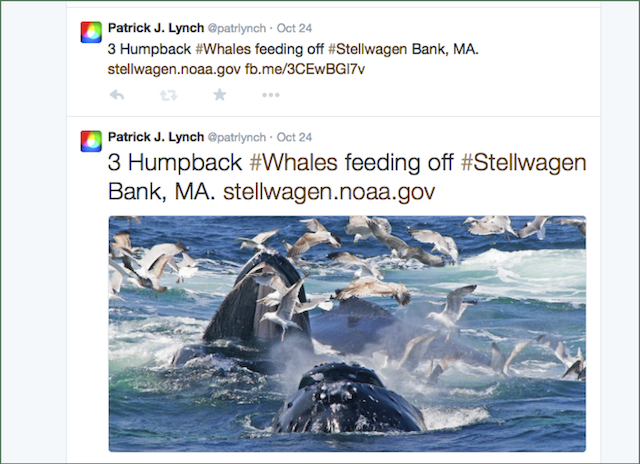

- Length: Data show that tweets of 70–100 characters or fewer are ideal, as they are more informative than a very short tweet, are quickly scanned, and leave room in the message for retweets that add comments, @username additions, and added metadata hashtags. Tweets in the recommended size range average 17 percent more engagement than very long or very short tweets.

- Linked media: Tweets with graphics get more engagement and retweets than plain-text tweets, but not all graphics are equally effective. You can link graphics as large as 1,024 × 512 pixels to your tweet, but linking large graphics is a bit pointless, as large graphics simply appear as links in a tweet—the user sees only a plain-text tweet and has to click on the link to see your large graphic. It’s a much better practice to limit your twitter graphics to what will fit within the Twitter stream, no larger than 440 × 220 pixels, so that your post now benefits from the eye-catching effect of the graphic in the Twitter stream.

- Hashtags: Twitter hashtags are a great way to call out your tweet to particular audiences or user communities. Many users habitually search for favorite hashtags as a way of cutting through the general Twitter noise to find relevant content. However, excessive hashtag use looks amateurish and calculated to game the system. Use no more than two hashtags on a tweet, and if you use two, make sure you keep within the 100-character guideline.

Because the average tweet lifespan is so ephemeral, most enterprises tweet at about twice the rate that they post to Facebook, or about three to six posts per day, and often more for news organizations, particularly when major stories are breaking. The ultimate metric here is your number of followers. Experiment with more frequent tweets, but if you tweet too often, people will begin to “unfollow” your account and your number of followers will drop accordingly.

The short lifespan of a tweet also presents opportunities to reuse good or important content, as most tweets have an engagement rate of less than 5 percent, often because most users simply didn’t see the tweet flow by at a time when they were not looking at Twitter.

The majority of very active individual Twitter users, including most enterprises, use some kind of scheduling service (Hootsuite, Buffer, Sprout Social) to at least partially automate their flow of tweets. Scheduling software like Hootsuite can be useful for “preprogramming” this evergreen curated content over several weeks or months, repeating good material at different times of day or days of the week, assuming that a reader who missed your original tweet on a busy Tuesday morning might happen upon it on a quiet Sunday afternoon.

Facebook ranking algorithms

Facebook users aged eighteen to forty-nine have on average about 250 friends, are connected to an average of 80 commercial, organization, or event pages, and create about 90 pieces of content a month. With such a heavy potential volume of posts on a user’s News Feed, Facebook has long used a proprietary set of algorithms to determine what posts from friends and brand pages appear on a given user’s News Feed. Originally Facebook called the algorithms EdgeRank, and although the company no longer uses the term internally, it is still widespread in the social media communications industry. Recently the social media community simply refers to the News Feed, or to News Feed algorithms, in describing Facebook’s filtering of what appears in the user’s News Feed.

In Facebook parlance an “edge” is any interaction with a piece of content within the Facebook universe. The original EdgeRank algorithm weighed three major factors to determine the likely relevance of a given post for a particular Facebook user:

- Affinity: A numerical scoring of the user’s relationship to the source of a piece of content. If the user frequently “likes” posts, comments on posts, or shares posts from a given source, the higher the affinity score, and the more likely that the user will see more posts from the same source.

- Weight: A ranking of common interaction types on Facebook. “Liking” a post takes little effort and gets a low “weight” score, but commenting on a post or sharing a post takes more user effort, and creates a higher weight score.

- Time decay: A simple measure of the time a given post has existed. The older a post is, the lower it scores in time decay, because the vast majority of user engagement with a post (likes, comments, shares) occurs within the first half hour of the post’s existence.

Since 2013 Facebook has moved away from the term “EdgeRank” in its internal communications, and now claims to weight as many as 100,000 factors in its News Feed algorithms determining the relevance of content to a particular Facebook user, although the original three weighting factors above still account for most of the algorithm’s results.

Staffing your social media team

Most organizations already have individuals or whole social media teams on staff and have an existing track record in representing the brand or enterprise. More often than not these teams are run as part of broader marketing and communications efforts, as those existing writing, strategy, and media skills are the most relevant to the newer channels of social media. If you have the resources to expand your team and social media efforts, consider media professionals with expertise in online graphics, photography, and short videos, as graphic media are often the key to higher engagement from readers.

If you are not already using stock photography agencies for visual material and simple illustrations, work with designers to establish reliable, high-quality sources of photography, as you will need new visual material almost every day. If you are not in a core media relations or communications department, try to establish good relationships with the media people in your company, as most larger enterprises produce a steady flow of news releases, product photography, and other material that you can repurpose to feed your social media channels.

Start small, and if your resources are stretched, then stay small. No law says you need to address every new social medium that comes along, as every new channel is a significant maintenance commitment. It’s much better to maintain a few high-quality feeds to Facebook or Twitter than to strain to produce mediocre content for half a dozen social media channels.

Recommended Reading

- Halvorson, K., and M. Rach. Content Strategy for the Web. 2nd ed. Berkeley, CA: New Riders, 2012.

- Kissane, E. The Elements of Content Strategy. New York: A Book Apart, 2011.

- Redish, G. Letting Go of the Words: Writing Web Content That Works. 2nd ed. Waltham, MA: Morgan Kaufmann, 2012.

- Rumelt. R. Good Strategy/Bad Strategy. New York: Crown Business, 2011.

- Shneiderman, B. Leonardo’s Laptop: Human Needs and the New Computing Technologies. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003.

- Wachter-Boettcher, S. Content Everywhere: Strategy and Structure for Future-Ready Content. Brooklyn, NY: Rosenfeld Media, 2012.

- Welchman, L. Managing Chaos: Digital Governance by Design. Brooklyn, NY: Rosenfeld Media, 2015.